Interview Eyal Weizman, Berlin 12/2002

An Architektur 06 Segal/Weizman: The Politics of (Israeli) Architecture

In summer 2002 your exhibit 'A Civilian Occupation' was withdrawn by the Israeli Architects Association from the UIA congress in Berlin, how did this happen?

Rafi Segal won the Israel Association of United Architects (IAUA) Young Architect of the Year award. When he was invited to take part in a limited competition to represent them at the International Congress in Berlin, he asked me to join in. We proposed to examine Israeli planning processes in- and outside the West Bank. We won the competition under a clear premise: we're going into an open-ended research process and will present our findings. At the same time I was working on a human rights report called 'Land Grab' for B'tselem - an Israeli human rights organisation. This obviously influenced our research greatly. When the organisers saw the result, they realised, that they could not exhibit or publish that and the project was stopped at the last minute.

The organisers didn't initially realise, what the research was going to be about?

Well, they knew about the subject. But what came out was a different approach that describes planning and architecture in Israel. Architects in Israel consider themselves to be more liberal and left leaning. The problem was, that this was the first time a direct and clear relationship was demonstrated between their work and human rights violations. This was more than they could take.

Was there any support for you from other architects?

Yes, of course, the affair really divided the architectural community in Israel. Strong voices, even within the Association of Architects were raised against the ban. There was a wave of support in the media and from the public in letters to the editors. Esty Zandberg, the reporter that broke the story, published seven articles in our support. It was like a wake-up call for architects.

When and under which circumstances did you start to be interested in the built environment aspect of the West Bank and to work on that issue?

At the end of 1995, after Rabin's assassination, I went to the PLO planning office near Ramallah asking to work there. I was a second year architecture student, and was given simple tasks, painting green areas and so on. Soon they realised, that being Israeli, I could obtain information that they had no access to. I was going to open public sources like university libraries, photocopying maps. I recognised that so much of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is actually manifested through the transformation of the built environment. It was quite obvious to get involved.

How did you pursue your research on the subject?

In 1999, Michael Sorkin was arranging the 'Jerusalem Conference' inviting Israeli and Palestinian journalists, architects, and theorists to Italy to speculate about possibilities for a unified city. From our perspective today, 1999 was a different time. There was much optimism, we were speculating about Jerusalem and feeling that we could actually make it work as an open city. What came out was a very optimistic book, documenting the zeitgeist. Today, I think, everybody who participated would be much more cautious.

How did your co-operation with B'Tselem start?

B'Tselem wanted to write a human rights report on the settlements. They had already compiled a few which had been dealing with quantifiable issues, statistics, land expropriation, international law, etc. I think, our joint project was perhaps the first attempt to tie-in particular issues relating the organisation of space, planning work with human rights violations.

Initially we aimed at a short statement, but as we gathered information, it grew. It is now a rather extensive publication titled 'Land Grab' in English, and comprises the history of planning in the West Bank and an analysis of the particular environment it produced.

Human rights violations are usually understood as the outcome of quick processes, military incursions, illegal arrests, any sort of straight, direct, violent damage. We demonstrated how human rights were violated as the result of long-term planning and construction.

The B`Tselem report was an attempt to write a human rights report spanning 35 years of Israeli occupation and tracing the gradual transformation of the landscape and the built environment. It is tracing human rights violations by means of another type of warfare, waged through architecture and planning.

Both 'A Civilian Occupation' edited with Rafi Segal, and 'Land Grab' are documents that incriminate particular architectural and planning processes and particular architectural forms we called the vernaculars of occupation. Both claim that particular formal manipulations and organisations, as carried out by architects and planners, are breaching human rights, and sometimes you could claim that war crimes are committed.

Is this formal organisation and manipulation a result of political strategy?

Absolutely. Political strategy transferred onto the ground has implications on peoples? lives. Perhaps it's useful to trace the process of the settlement project and its human rights implications.

During the first ten years of occupation (1967 to 1977) a succession of Labour governments used the settlements to secure the borders of vast (in proportion to Israel proper), newly acquired areas in the occupied territories. They built a line of military fortifications along the Suez Canal which constituted the Western cease-fire line with Egypt, called the Bar-Lev Line, and a series of moshavim and kibbutzimalong the cease- fire line with the Kingdom of Jordan - the Jordan River.

Palestinians did not settle in these areas, so friction was low. However there was continuous damage that has only became apparent lately. The Jordan Valley is hot and arid and the agricultural settlements were using up a lot of water from the Eastern mountain aquifer. This led to the drying-up of the wells of Palestinians living nearby and to the abandonment of arable land in large parts of the Eastern slopes of the West Bank.

In 1977 Likud came to power. 1977 is the year of a big transition in Israel. It is the first time that a conservative right wing party has control of the state. Initially, Likud had little self-confidence in its ability to retain power for long (in fact they only very occasionally lost power to Labour thereafter). Their idea was to complicate the terrain in such a way, that any succeeding Labour government would not be able to partition it anymore. The man in charge of the settlement policy was Ariel Sharon. His policy was in effect anti-Labour - and executed through complexity. Sharon dispersed settlements so that the territory would become most difficult to divide, and placed settlement points in between the Palestinian towns. As a retired general he picked strategic positions overlooking main roads, and the principal Palestinian centres.

Do you mean that these settlement are civilian, but their positions have been determined by military strategy?

Yes, it was the unique situation, where considerations of military strategy and national ideology overlapped in the personality of Ariel Sharon. After the lessons of the collapse of the line defence of the Yom Kippur war, he believed that only defence in depth would stop an invading army that attempted to traverse the West Bank, and not the line of Kibbutzim along the river. He therefore distributed settlements strategically from a military point of view, and then started a massive highway construction project to link them up.

There was a very famous High Court case in 1979. The Palestinians petitioned against the expropriation of their land for the creation of a settlement called Elon Moreh near the Palestinian city of Nablus. The proceedings of this case are fascinating. The High Court Judges had to decide whether a civilian settlement was of 'temporary military necessity', the only category, that allowed expropriation of private land. Judges were debating urban forms vis-à-vis military strategy to establish whether the settlement was essential for the security of the state.

They understood that the answer lay both in the location - what the settlement overlooks - and in its lay-out, the circular spread around a mountain top to allow maximum vision and supervision. The government argued that the settlement - although inhabited by civilians - was an effective fortification.

You are talking about the complexity of the terrain. How is this complexity, created by the settlements, visible, and what are the results?

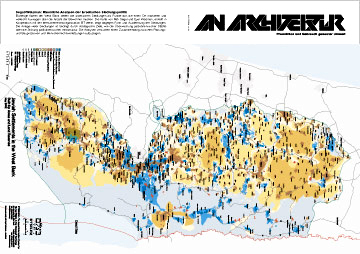

The results are a complete destruction of any possibility to partition the surface. The map I produced for B'Tselem shows how and why the 'Politics of Verticality' had to be developed. Furthermore, the map exposes the success of the settlement project which has succeeded to radically change the geography of the area in just 35 years. It shows, how a very committed government policy and intelligent planning can bring 200.000 settlers into the West Bank (excluding Jerusalem), creating facts that paralyse all Palestinian territory. The terrain has become fragmented into camouflage-like patches of enclaves without continuity between them. A solution based on partition can no longer be achieved on such a surface without a complete transformation amounting to the removal of settlements.

Although they attempt to build a fence that separates Israelis from Palestinians, and find its optimum route - a 'perfect' line - a line to take all the blue spots (settlements) to one side and all the brown spots (Palestinian built fabric) to the other - is not possible with the current state of facts on the ground. It is the failure of the surface to allow for a linear separation that had necessitated volumetric solutions.

How is the Palestinian territory being paralysed? And what are the repercussions for the occupied areas?

In order to understand the full scope of the spatial manipulation of planning in the West Bank we need to identify its constituent dimensions, i.e. point, line, surface, and volume. The process that ends in the polarisation of the West Bank starts with selecting points (across the terrain) where force is applied. This strategy of settlement prefers location to essence. A point has no dimension, apart from its location along an x and y matrix, and its latitude (z), which is usually determined by strategic-military thinking: on a hilltop, as observation point to overlook vital interests - a main traffic artery, a cross-roads, or a Palestinian town.

Multiplying the civilian settlement points that function as optical devices utilises the civilian presence as vanguard observation posts. The settlements are also focal points from where the army can re-deploy and re-organise in case of need. In this fashion, with determined strategic aims, the whole terrain could be controlled and even paralysed at will.

Therefore a discussion focusing on percentages of land is misleading. Jeff Halperstated this very well in his article 'The Matrix of Control', claiming that a matrix operates by presence in strategic areas rather than by continuous presence across large terrains. Looking at the series of plans proposed for respective peace initiatives from the Allon Plan of ?67 through to the current Sharon Plan, we see that public debate is focused on percentages of land each side is willing to cede, like trading equities or currency to pay for peace. But statistical thinking is misleading, we aren?t talking about a cake that can be neatly sliced up, but about the outlines defined as borders. And if you try to comprehend the formal aspect of territorial solutions and proposals, you understand, that there are specific maps with particular borderlines that would render even a 97 % solution unfeasible because you can paralyse the whole terrain with the remaining three percent, and get a non-viable state.

Did your interest in form evolve from that observation?

No, Rafi and I started out with formal analysis, and that was one of our conclusions rather than a starting point. Wanting to be as accurate as possible, we put all the available maps and plans of settlements on the wall and looked at the shape of the way settlements were occupying the topography and how they were positioned vis-à-vis Palestinian villages. Our work was like that of an archaeologist looking at the material traces - say a corner of a building, and recreating the forces and processes and ideologies they served and represented.

We became aware of recurring patterns through our ability as architects to read plans, and we traced back and identified the forces that created those patterns and forms.

Did you initially expect to find those forms that violate human rights?

When we started working on 'Land Grab' there wasn't a thesis yet. We proposed to investigate planning both as a process and as a formal physical transformation. We observed the process of planning in bureaucratic terms and the problems inherent in the injustice of that system. Then we looked at the material reality and the way it functioned as strategic tool.

We had no preconceptions. Simply by taking into account both the planning process and its material outcome together with the damage this inflicts, you realise the direct relationship between the very peculiarity of how the terrain is organised and a violation of human rights. Now, the question must be posed who is responsible? If there is a crime, who is a perpetrator? The issue therefore calls for a different critique of settlements. Many left-wing organisations in Israel claim that the problem with the settlements is the very fact they are built beyond the Green Line. But for us this is merely the starting point. We accept that they are illegal on that basis - but there is a further degree of responsibility because it is also the way they have been designed and built - in the very organisation of the terrain - that crimes are committed. The other approach is one that does not look at maps, plans, forms, architecture and planning.

To give an example: The settlement city of Ariel, close to the Palestinian town of Salfit, has a formal lay-out that does not serve the population, but extends elongated and thin in order to achieve various other objectives. One aim is strategic, and the settlement spreads itself thinly along a strategic highway. Another reason for the banana shape is to create the longest possible wedge between the town Salfit and the other villages to the North, which are a vital part of the regional economy. The settlement also surrounds the Palestinian town from three directions with the clear attempt to suffocate and impede its growth - the ultimate aim is to compel Palestinians to migrate from the region. A single-family house is as damaging a weapon as a bulldozer that destroys other homes, or a soldier shooting a machine gun. This puts architecture on the same level as other kinds of weaponry, like tanks, bulldozers, guns etc.

These things can be seen on maps, because they have formal dimensions. It is in the form of the settlements that the effect on Palestinian human life is most strongly felt - not in the mere presence of the settlement. But that doesn't mean that there is a better way than others to design a settlement. Our point is just that there is another level of responsibility.

Would you say architects have committed crimes?

Yes, international law has been broken on the architects' drawing boards. The decision to draw a line here and not there has consequences. The kind of gesture with the pencil or with the mouse that you make has an effect on peoples' lives, and these could be quantifiable in terms of international law. In the West Bank we are dealing with a premeditated intention to create material damage through the way space is organised. Those who bear the consequences of this warfare are always the Palestinians. Breaches in international law can be traced to the Rome Status of the international Criminal Court or the ICC. There are some clauses under the war crimes section under which architects could in theory face trial.

In addition to that, Israeli planning law itself is breached on several occasions. Planning is required to be undertaken in order to serve the 'public'. To design in such way that aims to take as much of somebody's land or to suffocate an existing town are violent acts. Israeli planners use a strange definition of the term 'public', for them the 'public' always includes the Israeli Jewish society whilst considering Palestinians merely as individuals never as public themselves.

I think that moving critique from a cultural, academic debate into a legal debate would be very important for architecture as a praxis. We might for the first time discuss crimes performed through architecture, not on a theoretical level, but on a practical level, and start moving clearly and decisively in litigation against architects, employing judicial techniques.

Conventional critical tools from within the cultural, academic, and vocational sphere etc. are not powerful enough. If architecture wants to play on the same court as military strategy, politics etc. it must answer to the same rules that apply there, meaning a legal framework. I recommend that architects are taken to court not for the failures of their action, if their house collapses or if they go over budget etc., but that they should be taken to court for what they actually meant to do, for the success of their project. If you define crime as we did in 'Land Grab', you must consequently compile a legal case against those who have perpetrated these acts.

What would be the consequences for an architect if a violation of human rights was stated?

Human rights violations are the matter of international institutions and are acted against between states. Unlike human right violations, committing war crimes may bring an individual to face charges. The problem with international ethics and law is it often becomes a means by which powerful states observe and monitor weaker states in which they have a vested interest. The US, for example, is pressing issues of human rights in order to justify foreign intervention, just look at Iraq - it violates some human rights in order to claim to restore others. There are problems with looking at things purely from the perspective of humanitarian intervention and international law. Sometimes the process of regarding humanitarian issues in isolation disregards basic political rights and reduces societies to populations - objects of care and welfare.

I am not against taking action on the basis of human rights. But we have to know how to deal with these issues with caution.

Has your research included the other side of the conflict, i.e. Palestinian locations and planning?

Going back to the map, we previously concentrated on the investigation of the blue stains: Israeli settlements, Israeli planning practices, Israeli built culture, Israeli planning laws, legal system, etc. We did not feel qualified to comment on Palestinian built culture. But finally did it regarding the effect on Palestinian villages and cities of Israeli building and military practises.

What we had to understand first was that the urban terrain can considerably reduce the advantage of a state-of-the-arts army over a guerrilla fighter because the sophisticated military equipment simply doesn?t work in a dense urban environment. Now there is an incredible effort by many armies, as well by academics, to understand the city as a strategic site, sometimes even as a strategic weapon itself.

The Israeli army has been confronted by intense urban conflict for almost three years. To train, they built model cities that look like refugee camps or practise new techniques within Palestinian cities. The underlying idea about that new type of combat is, that there is a clear relationship between the way a city is built, its material organisation, and the possibilities of governing and policing it. A kasbah-like city with connected houses, winding streets and narrow alleyways become a trap for the military, as well as being difficult to maintain a hold on. This is the case of the Palestinian refugee camps in the West Bank.

What were the army's conclusions from this?

During the Israeli operation 'Defensive Shield' major Eyal Weiss, the commander of the Special Forces unit came up with the idea of moving about the city, not in the streets but through houses and walls.

A whole division of air-borne infantry went swarming through the refugee camps Tul Quarem, Jenin, Balata, carving out paths within the urban fabric. They were realising that a sniper would most likely shoot anybody who came out on the street. So there was nobody in the streets, only armoured vehicles. The infantry was moving from one private apartment to the next, breaking down walls with hammers or explosives - drilling three-dimensional paths through the dense Palestinian fabric. This is a negation of the existing urban fabric, replacing it with another system, imposing another circulation system on it.

On the larger scale, there were the bulldozers carving up roads and creating large openings within the camp. These were working in almost a similar fashion to the way Haussmann rearranged Paris for military reasons. When the Israeli military carves a grid through a refugee camp, like in Jebalya in 1971, they have in mind a specific kind of urban design.

I think this is the only way to understand the destruction of Palestinian cities during operation 'Defensive Shield' last spring; as an attempt to redesign the Palestinian city, to make it more controllable and governable. But so far it was reported and analysed by almost everybody as a statistical issue, relating to numbers of destroyed Palestinian homes. Here again, I believe that formal analysis is important on an architectural level, of this kind of tunnelling, drilling, or worm-like advance through constructed urban mass and the urban surface with bulldozers bursting open new thoroughfares, openings, and axes through the city. It can only mean that the military believes that the city can be conquered by redesign, that urban form is directly related to military power.

'Civilian Occupation' is focused on the role of architects and planners regarding Israeli settlement politics. What is central to your project 'Politics of Verticality' that was published in April?

'Politics of Verticality' concentrates on demonstrating the inadequacies of conventional two-dimensional maps to understand the complexity of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. This conflict happens in three dimensions. The borders it generates are acting themselves out in volume rather than on the surface as in other places. The Politics of Verticality is the mental and physical partitioning of the West Bank into two separate and overlapping national geographies.

Between the first Oslo Accord (1993) and the Camp David negotiations (2000) new forms of sovereign boundaries were invented. The Palestinian Authority was given control over isolated territorial 'islands', whereas Israel retained control over airspace and the sub-terrain. The sub-terrain and the sky were thereafter seen as separate rather than continuous and organic constituencies to the surface of the earth. But beyond its mere presence in the realm of ideas, the creation of in-situ mechanism and large-scale infrastructure projects have thereafter carved volumetric paths in a newly defined sovereign bulk. My work on it is a critique of the reliance on maps, as an absolute tool by which politics are conducted. The borders don't really work on two dimensions, and various technologies are applied to make use of volume, like tunnels and bridges that span over or dive under alien territories. These are different sorts of peace technologies that aim to separate Israelis and Palestinians along three dimensions. Subsequently the path of the border becomes very complex and it draws a volumetric path.

Yet the thinking about the borders remains traditional. The border is not a fence, the border is still the absolute limit of a legal and control system; it marks the formal dimension of the spatial extent of the law. What happens here, is that those three-dimensional borders are borders in a very traditional sense played out in a very untraditional and creative way. This in my opinion is the wrong approach to manage the conflict. Instead of manipulating the trajectory of the border one has to re-examine the relationship between border and law.

These days, when you think about globalisation, diasporadic communities and so on with displaced minority communities, it seems that the spatial confinement of law is becoming less and less relevant. A new relationship between the definition of territory and the definition of law can be drawn up, and perhaps the exceptional conditions of the West Bank could help develop this tool. This is where 'Politics of Verticality' is leading to.

Is there an attempt to represent the 'Politics of Verticality' in a three-dimensional model?

In order to understand and conduct political negotiations you need a three-dimensional map or territorial model if you prefer, and I was working on producing a semblance of it with Reed Kram. We were proposing a three-dimensional interactive map that could help understand how the different layers are superimposed upon each other. Here, the West Bank is described by a succession of maps, none of which corresponds to the one on top or underneath, each one has its own logic and produces its own boundaries. The map of infrastructure and the map of water resources do not align with the political map. The map that describes the electricity supply grid across Israel and Palestine is totally at odds with any kind of political solution proposed on the surface itself, they just slip over each other.

Maps are never objective, they are intrinsically political in what you choose to show and how you show it, and what you choose to omit. If people conduct policy on the B'Tselem map, they have to deal with the information we want to show them. Maps can influence both public opinion and policy makers by making them conduct abstract politics on the basis of the formal product you provide them with.

Both the B'Tselem map and those other maps will become tools according to which policy will be made. But as we're talking about something which is not historical, but still in the process of its making, every single data you add becomes a tool for someone to work with.

We would like to take up your notion of the tool. Do you expect those three-dimensional models to become a tool during peace negotiations?

I don't think that showing borders in three dimensions holds a potential for a solution, but if this 3D mapping is used in negotiations, the nature of the solution would be different. The nature of the tool would change the nature of the product. And in this case the product is a border.

You talked about the border as an edge to the legal system and claim that now it no longer works in two dimensions, you have to draw different layers, where the borders look different; but does the hard edge exist in the three-dimensional map? Or is there an undefined zone, a blur?

What is exactly the problem, the three-dimensional border is a border in a very traditional sense. It delineates the physical outline of the extent of a law which is subsequently manifested in very complex spatial entities. With all the creativity invested into the path of the border nobody actually considered the border in relationship to law; basically what they have done is to draw the physical trajectory in a very obscure and bizarre way. All those solutions are nonsense, they will never work. The three-dimensional model shows the exhaustion of all possibilities relating to the idea of a border in relationship to the space. Nowhere else in the world has a border become so complex. So perhaps now the time has come to re-assess the relationship between border and law. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is a territorial conflict that can't be solved territorially, or formally. If the solution insists on partition you create a state which is not viable, geographically and economically. It is nonsense in the long run to think about Israelis and Palestinians living in two separate states.

In Michael Sorkin's book 'The Next Jerusalem', some contributors advocated a solution based on an open city that is the capital for both nations. There are two municipalities; one municipality is regulating the life of the Palestinians, one municipality regulating the life of Israelis, and one municipality over it. Meaning that the jurisdiction of these municipalities is not territorially based. Jerusalem is a microcosm of the whole country, the whole country is fragmented, just like the neighbourhoods of Jerusalem. I think that the Jerusalem model could be applied to the whole country, perhaps we have to start thinking about the entire Israeli-Palestinian terrain in urban terms rather than territorial terms. It is small enough to be considered as one big city, or at least one metropolitan system.

Sharon Rotbard said about Civilian Occupation that its critique is not merely about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict but, for example, addresses architects who work for big corporations as well. You have used the term laboratory to describe the overlap between a specific local situation and international architectural trends?

Israeli architecture and planning has always been a mirror of international developments. It always took contemporary utopian ideas or current architectural trends and anchored them to the context of the territorial conflict. The settlement projects started in the early eighties or late seventies, and coincided with the retreat of the American middle class, fencing itself in behind walls, that kind of new urbanism or gated communities. In Israel they are much more extreme, because Israel is small and its violent intensity accelerates the fates of all those architectural trends. In a sense this is what makes it a laboratory. I think we can definitely see settlements as a metaphor for an extreme meeting between third and first worlds. The confrontation is intense and it happens in close proximity of one another, just like in Rio De Janeiro, Mexico City, Johannesburg etc.

We are in danger of seeing this research only in the local context of this particular conflict. But is there really a big difference between a by-pass and highway in Detroit cutting up black neighbourhoods? The highway without exit and a by-pass road are the product of the same realisation that one can use planning as a weapon.

Currently many case studies and projects focus on extreme urban situations. How would you describe the difference between your approach and Rem Koolhaas' case studies?

There is something about the territorial research of Rem Koolhaas we find problematic. It lies with his particular way of analysis, with all its brilliance and cynicism. Koolhaas' methodology is the transfer of the observation into a series of concepts and into design-tools to be applied somewhere else - the deterritorialisation of the conditions one observes. But our approach does not seek to 'learn from the West Bank', we are not fishing for design concepts. This is not an applied research. We are describing something which is grave, which is a crime that has to be addressed on site. Koolhaas? attitude implies that you cannot resist capitalist forces, but must accept and play with them. The methods that were working with so well during the nineties can no longer be applied now, at least in our case. Now, it seems that a different sensibility and a different degree of responsibility is called for in architecture.

Where can you see opportunities for architects to get involved politically in the context of this responsibility? How can you avoid being trapped into affirmation or irrelevance?

The point I am trying to make by analysing the territory of the West Bank is that form matters and it must be brought to the forefront of the political discussion. I think that for too long the people that are dealing with the political and economic aspects of architecture have been neglecting form, and concentrating on abstract processes and forces. I try to use statistics as little as I can - there is nothing wrong with statistics as such - but for the purposes of architectural and territorial research it has tended to divert attention away from form. People argue whether the destruction of Jenin amounts to a war crime because of the numbers of homes destroyed, but when you look at the shape the destruction took, the picture becomes much clearer. The urbicide of Jenin was an attempt to subjugate a population on the basis of redesigning its habitat.

What is true for settlement design is true as well for urban warfare. It's not that I don't care or grieve at the loss of life and property - that is obviously so, but counting and quantifying has been overestimated as a mechanism of describing an objective truth. When human rights organisations go to Jenin and count houses that were destroyed, they don?t understand what happened there. When people add up the respective percentages on the West Bank, they can't understand what it is all about.

Compared to lay people, professional architects have a sharpened sense of formal observation, and it is our responsibility to take this ability to help make people understand the repercussions involved in formal aspects of politics, law, planning, as well as in patterns of destruction.

Since I was in conversation with Ron Pundak who is one of the architects of the Oslo Accord, we were sitting over a map. He was trying to show me a path for a border, which could preserve existing settlements on the Israeli side and find a volumetric solution for contiguity with tunnels and bridges. We were looking at one of the plans, and agreed that it looked really ugly. That was a strange observation - when talking about borders who cares about beauty? What does beauty mean at all? The lines were contorted, long, and sharply meandering. The conversation turned to architecture, and we discussed the well-drawn plans of Frank Lloyd Wright. Did it matter that the plan looked good from above? Nobody sees the plan; the plan is the one invisible thing in architecture. Does it matter that the line of the bathroom meets the line of the bedroom at the other end of the building? I don't know if it does, but finally, the plan is the key to its spatial organisation, guides the order of use and functionality of a structure, and there it all lies. Going back to the national territorial scale, I think that the reasons for feeling repulsion about the ugly lines is based on the fact that the form was not viable in functional terms. It wouldn't have allowed a state to function formally.

If we supplement the discussion of percentages with a discussion of form we could understand the history of this conflict better, as well as learn how to act with more precision. Ultimately the path a line takes on the map gives you either a functioning state or a non-functioning state.